The Snapshot Problem

Why smart people can look at AI and see completely different realities

Last week, my partner Rob shared an essay in our Slack channel — Matt Shumer’s “Something Big Is Happening.” The next day, he dropped a second link: Will Manidis’s “Tool Shaped Objects.” His comment: “This is a much more measured rebuttal.”

The first described a world where you walk away from your computer for four hours and come back to finished software. The second called the whole phenomenon a modern version of FarmVille — people performing the ritual of productivity without producing anything.

We went back and forth for a while. Not because we disagreed, exactly, but because we both recognized something uncomfortable: each essay was describing something we’d actually seen. The optimistic version matched what I was experiencing building AI products and incorporating AI into how we work. The skeptical version matched what we were hearing from founders whose AI pilots had quietly stalled.

We were both right. And so were the two essays. The question was why two descriptions of the same technology could be so completely irreconcilable — and what that meant for every investment decision, hiring call, and strategic bet being made right now.

The debate that’s not really a debate

If you’ve been anywhere near the AI conversation this past week, you’ve probably encountered the collision.

On one side: Matt Shumer, an AI startup CEO, published “Something Big Is Happening” — describing a world where you can walk away from your computer for four hours and come back to finished software. Where the gap between what AI can do and what it couldn’t do last month is so dramatic that anyone paying close attention can feel the ground shifting.

On the other: Will Manidis — who founded a language model company, sold it, and now runs AI projects at a large healthcare technology firm — responded with “Tool Shaped Objects.” He opens with a beautiful analogy: a master-forged Japanese hand plane that costs thousands of dollars and takes days to set up — and is, in the economic sense, worthless, because a power planer does the same work in a fraction of the time. The hand plane exists so the setup can exist. His argument: most of what people are doing with AI right now is closer to that hand plane than to a power tool. The consumption is the product. The setup is the practice. It’s FarmVille at institutional scale — click anywhere and the number goes up.

His core concept:

“I want to talk about a category of object that is shaped like a tool, but distinctly isn’t one. It produces the feeling of work — the friction, the labor, the sense of forward motion — but it doesn’t produce work. The object is not broken. It is performing its function. Its function is to feel like a tool.”

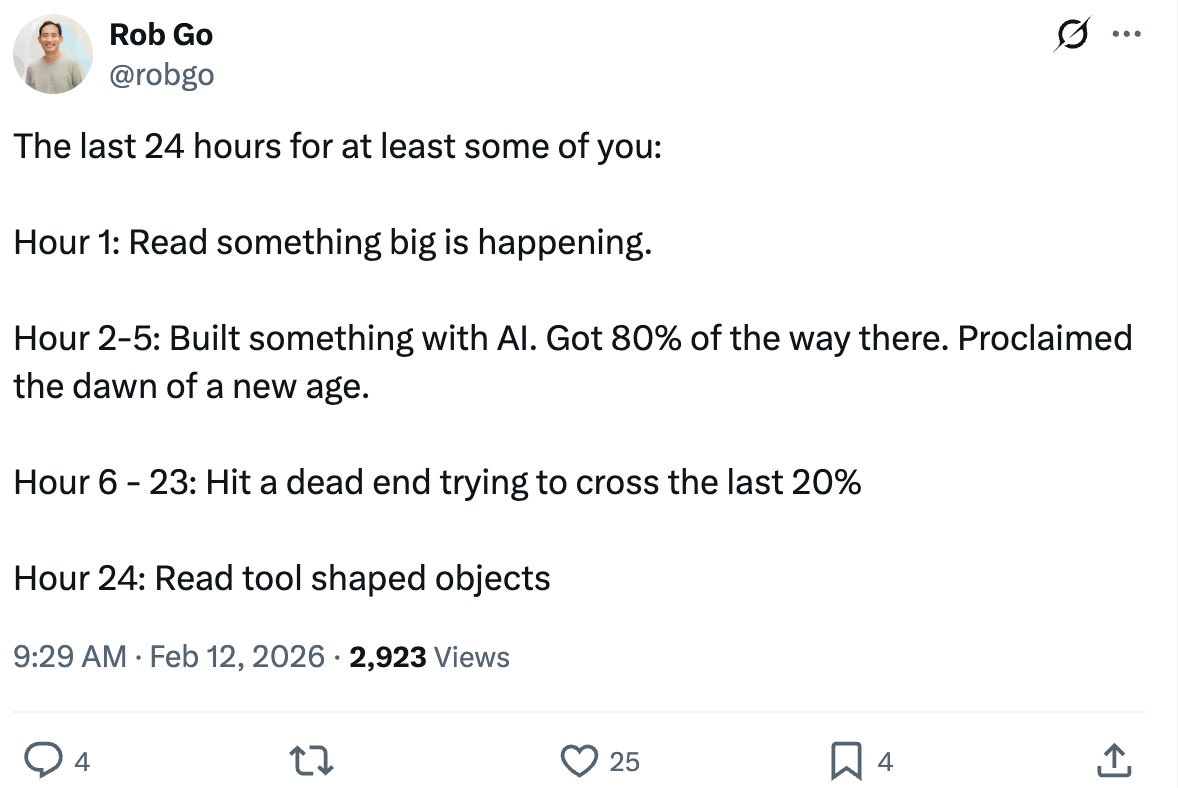

My partner Rob captured the whiplash perfectly in a tweet:

The internet did what the internet does. People picked sides. “Something big IS happening” vs. “wake up, it’s hype.” The discourse calcified into a binary that neither author intended.

But here’s what struck me, watching this unfold while living in both worlds — building AI products while also evaluating AI startups and incorporating AI into our investment workflow: both essays are describing real things they’ve actually experienced. The contradiction isn’t between their arguments. It’s between their vantage points.

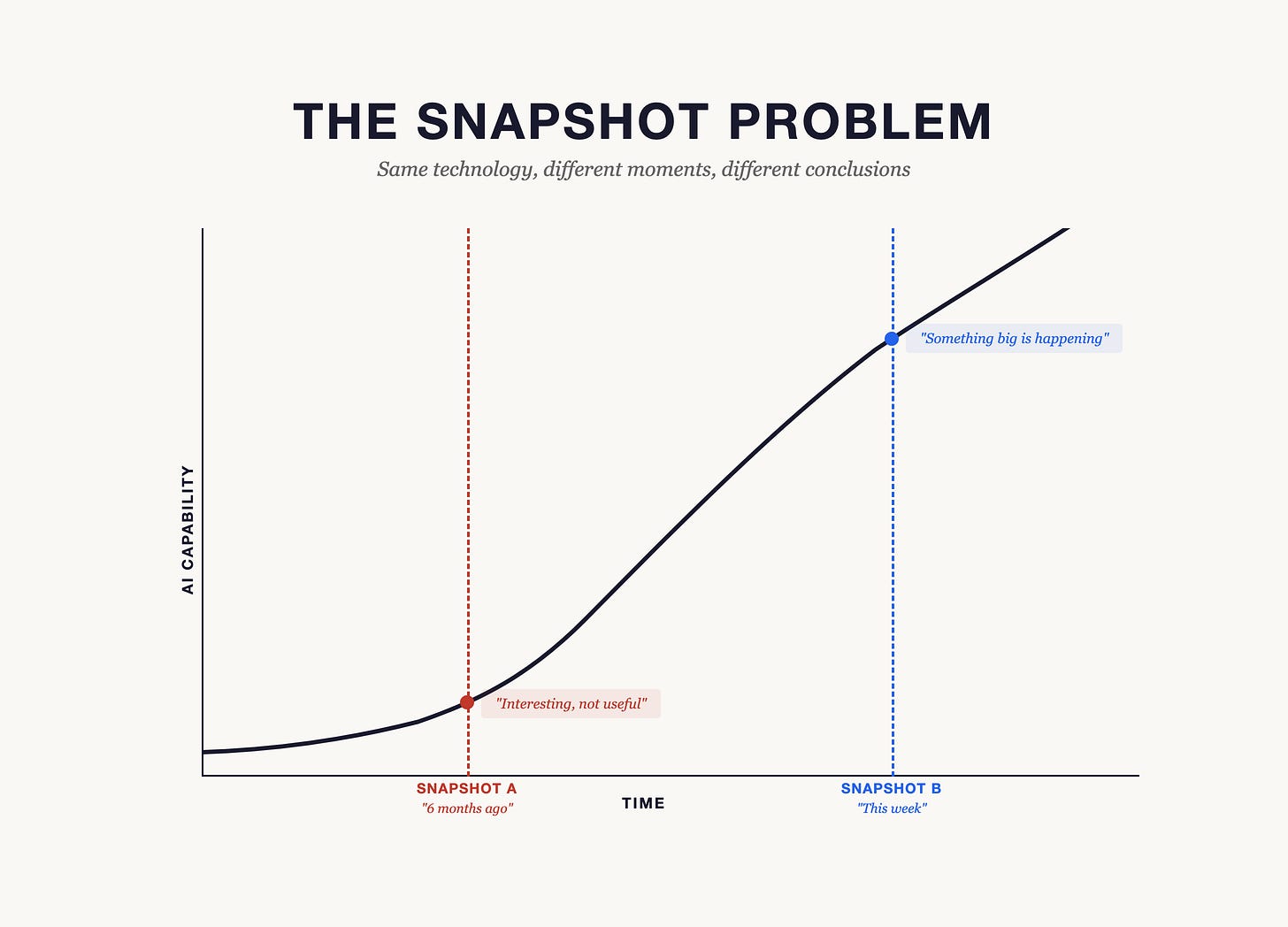

It’s not a disagreement about facts. It’s a disagreement about timestamps.

Shumer is updating his understanding of AI capabilities daily. He’s building with the latest tools, running into their edges, watching those edges recede week over week. When he says “something big is happening,” he’s comparing Tuesday to last Tuesday — and the delta is genuinely dramatic.

Manidis is comparing AI’s promises against the standard he applies to production software in healthcare — and against a more philosophical question: is the work being done, or is the experience of work being performed? When he says these are “tool shaped objects,” he’s pointing at something real: teams building agent systems of breathtaking complexity whose primary output is the existence of the system itself. And he’s careful to note that the line between genuine tool and tool-shaped object “is not a line at all but a gradient.” He’s not saying AI is fake. He’s saying most people can’t tell when they’ve crossed from one side to the other.

There are real reasons beyond timing for the divide — differences in risk tolerance, in what counts as “production quality,” in how much you trust systems you can’t fully verify. Manidis is asking genuinely important questions about whether the experience of productivity is being mistaken for productivity itself. But I think a significant share of the disagreement comes down to something simpler: they’re holding snapshots taken at different moments on a rapidly moving curve.

This is the pattern I keep seeing — not just in public debates, but within our team, in conversations with founders, and in the gap between what I read in pitch decks and company updates versus what I experience building every day. The real divide in the AI conversation isn’t optimist vs. skeptic. It’s frequent updater vs. infrequent updater. And that divide explains far more than ideology does.

Why snapshots freeze

The reason this matters isn’t that some people are more “plugged in” than others. It’s that updating your understanding of AI has an unusually high setup cost — and that cost is largely invisible.

You can’t just “try AI” by opening ChatGPT once and asking it to write a poem. That gives you a snapshot from 2023 that tells you almost nothing about what these tools can do in February 2026. The meaningful experience — the kind that actually shifts your mental model — requires investing hours in setup. Configuring a project. Loading context. Building a workflow. Failing, adjusting, and trying again.

When I talk about AI with friends — smart investors, experienced operators — I keep getting the same request: “Can you just give me some pointers on how to get started?” These are people who evaluate and work with technology for a living. They’re not behind because they’re less intelligent or less curious. They’re behind because the activation energy to move from “I’ve read about AI” to “I’ve experienced what it can do this week” is genuinely high. A few pointers won’t bridge that gap. It might not even be the right starting point.

This is why the debate feels so intractable. The people arguing “something big is happening” can’t understand how anyone could look at this technology and not see it. The people arguing “tool shaped objects” can’t understand how anyone could look at this technology and be impressed. They’re both reasoning correctly from different datasets — one collected yesterday, one collected months ago.

The tools themselves are moving under your feet

There’s a related pattern that makes this worse: the tools don’t just improve gradually. They leap.

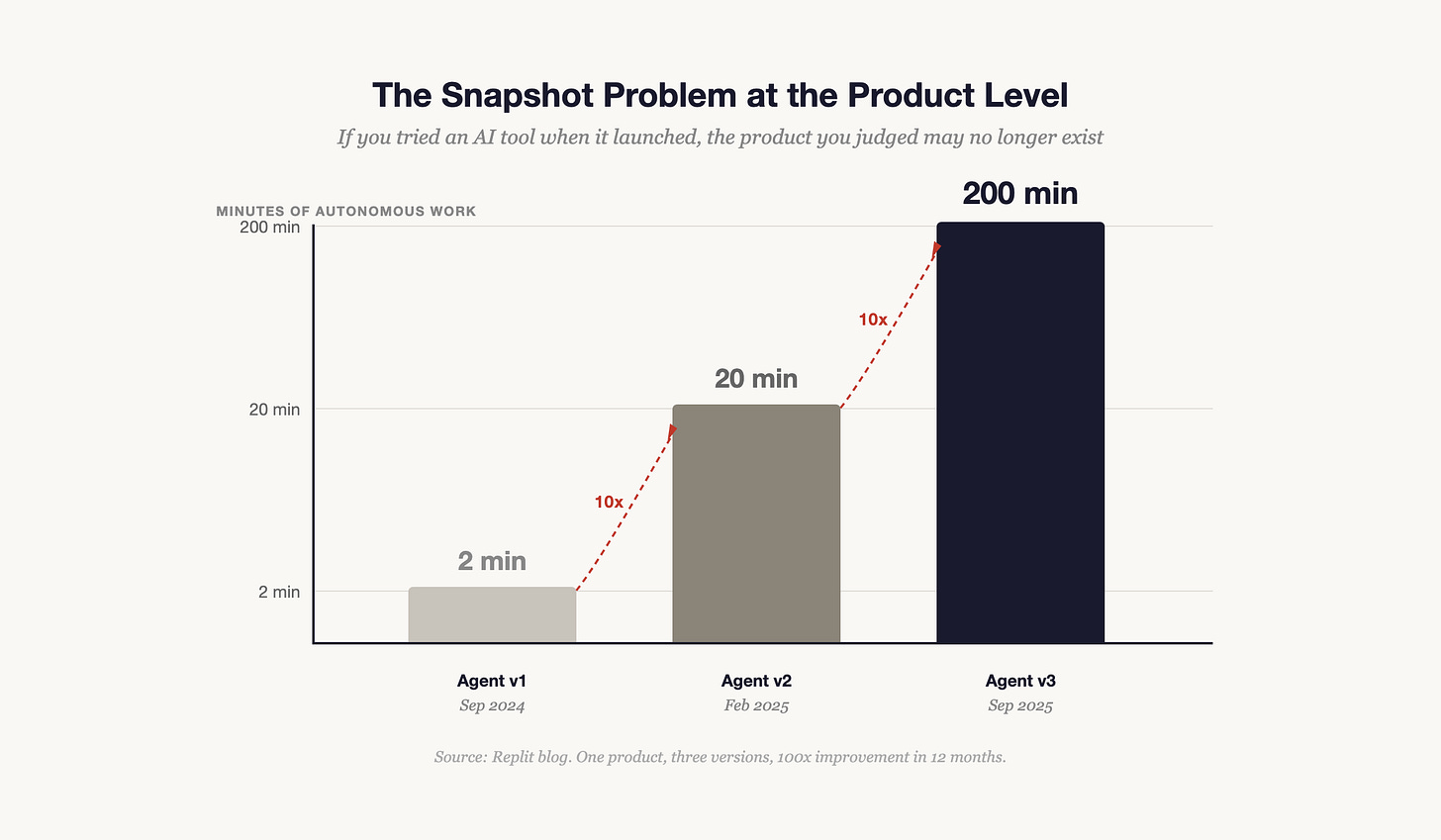

Jason Lemkin, the founder of SaaStr, described this on Lenny’s podcast in January. The episode is about how he replaced most of his sales team with AI agents — and his broader point is that most people still don’t understand how fast these tools are moving. To illustrate, he mentioned Replit’s AI agent — not as an endorsement, just something he’d been testing after seeing it on X. His experience tracked across three product versions: Replit Agent launched in September 2024 and could work autonomously for about two minutes. V2 arrived in February 2025 and extended that to twenty minutes. V3 shipped in September 2025 with up to two hundred minutes of autonomous work — a hundred times the original.

If you tried Replit Agent when it launched and thought “this is interesting but not useful,” that was a fair assessment. If you’re still holding that assessment eighteen months later, you’re making decisions about a product that no longer exists.

This is the snapshot problem at the product level. The tools themselves are changing fast enough that your experience from six months ago may be describing a fundamentally different product. And it’s not just Replit — Claude Code, Cursor, Codex, and a dozen other tools have gone through similar leaps in the same window.

I see a different version of this in my own building. The discourse on X loves the “walk away and come back to finished work” narrative. What actually happens is more nuanced: you walk away and come back to a strong first draft. If your quality bar is low, that’s exciting. If your bar is high — if you’re building something with real users, where mistakes have consequences — that first draft is the starting point for a conversation, not the end of one.

The people who update their snapshots regularly have internalized both of these patterns. They know that “AI can’t do X” often means “AI can’t do X yet, and yet might be next week.” They also know that “AI can do X” often means “AI can do a solid draft of X that still needs human judgment to finish.”

The Slack message that captured all of it

When the Shumer and Manidis essays were making the rounds, Rob and I were going back and forth on Slack about what was actually happening. And I found myself writing something that I think captures the honest position better than either viral essay:

“I think both extremes are true. Many are just doing the setting up for the sake of it, while many others are genuinely doing more productive things because of it. But the diffusion will definitely take a long time, precisely because I think it’ll stay quite complex for a while.”

That’s not a fence-sitting take. It’s a description of what you see when you update your snapshot daily while also maintaining the quality standards of someone who’s shipped products to millions of users. The capability is real. The complexity is also real. And the gap between them is where the interesting work lives.

This is what “Ground Truth” has always been about — the space between what AI can do and what it actually does in practice. The Shumer/Manidis debate isn’t a flaw in AI discourse. It’s the most visible symptom of the gap that defines this entire moment.

What this means if you’re making decisions

The practical implication is uncomfortable: your assessment of AI is primarily a function of when you last updated it, not how smart you are about technology.

This matters because the people making the biggest decisions about AI — allocating capital, restructuring teams, setting strategy — are often the people with the least time to update their snapshots. A CEO reading a quarterly industry brief is working from a snapshot that may be 90 days old. In AI terms, that’s a different era.

Three things follow from this:

Your snapshot has an expiration date. Whatever you believe about AI today is a function of when you last invested real time experiencing it — not reading about it, experiencing it. If that was more than a few weeks ago, your mental model is stale. Not wrong, necessarily. Stale. Like checking a stock price from last quarter and making a trade.

The debate is less ideological than it looks. When someone says “AI can’t do X” and someone else says “I just did X with AI yesterday,” the first person isn’t dumb and the second person isn’t lying. They’re describing different versions of a technology that changes faster than most people’s update cycles.

The real competitive advantage is update frequency. The founders, operators, and investors who are making the best AI-related decisions aren’t necessarily the ones with the deepest technical knowledge. They’re the ones who are regularly investing the setup cost to experience what these tools can do now — not last month, not last quarter, now.

The river and the photograph

There’s an old observation that you can never step in the same river twice. AI is moving fast enough that by the time you’ve formed an opinion about it, the thing you formed an opinion about has already changed.

The Shumer/Manidis debate will fade. Another one will replace it. And it will have the same structure: two groups of smart people, arguing past each other because they’re describing different moments on the same curve.

The question isn’t which snapshot is correct. It’s how recently you took yours — and whether you’re making decisions based on a photograph of a river that has already moved.

Previously in Ground Truth: The Trust-Utility Curve explored how earning AI’s trust (and giving AI yours) follows a specific, climbable curve. The snapshot problem is one reason that curve is so hard to see — if your last experience was V1, the curve doesn’t look worth climbing.